Aubrey Eveleigh describes the Albany graphite deposit in northeastern Ontario “as a real freak of nature.”

“We never expected to find something like this,” he said. “I spent my entire career exploring for base metals and gold for the most part, so this is kind of new. I had never seen anything like this in my life. Neither did any geologist I knew.”

Eveleigh, president and CEO of Zenyatta Ventures, a junior miner based in Thunder Bay, was intrigued by a “whopping” electromagnetic conductor picked up by an airborne survey 30 kilometres north of the Trans Canada Highway near Constance Lake First Nation and Hearst.

“There’s no outcrop in this area, so there’s nothing on surface to suggest what this was. We thought it was massive sulphide until we drilled into it and intersected hundred of metres of graphite breccia.

“The way Dr. Andrew Conly of Lakehead University describes it, a billion years ago, there was a rifting environment here. We are on a major suture or fault zone that was part of the mid-continent rifting and that conduit tapped the mantle. The carbon … came up in the form of CO2 and CH4, and … crystallized into what it is today: pure crystalline, fine grained carbon… so it’s volcanic and igneous in origin unlike all the graphite deposits in the world today, which are flake graphite deposits.

“Flake graphite forms from a sedimentary process. It’s basically organisms floating around in an ocean. They die, settle to the sea floor and eventually get buried or sedimented. The material is subjected to temperature and pressure and turns into graphite. Then through plate tectonics, uplifting and erosion, it gets exposed at surface.”

Albany graphite has fewer impurities than flake graphite.

“We have silica and feldspar attached to our crystals, but they come out easily using floatation and sodium hydroxide, leaving us with 99.9 per cent graphite,” said Eveleigh.

“Flake graphite has a lot more and varied impurities, so they have to use very nasty acids that are dangerous to deal with and toxic to the environment.” Processing flake graphite is also much more expensive.

Zenyatta Ventures has had its graphite tested by Japanese, Israeli, South Korean, European and American companies for applications in batteries and electronics, as well for an additive in concrete, plastics, aluminum and rubber.

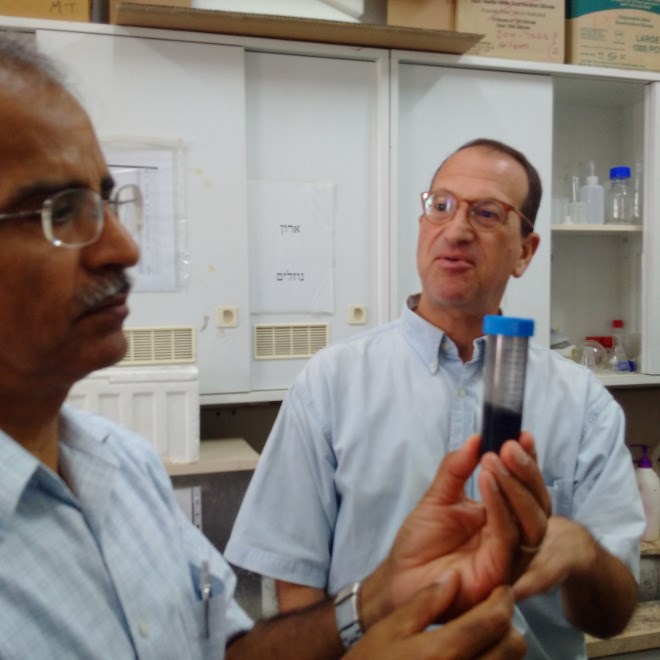

“The material converts to graphene easier than anything they’ve tried,” said Eveleigh. “The first institution to tell us this was Ben Gurion University in Israel.”

Graphene, discovered in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov at the University of Manchester, is a thin flake of carbon just one atom thick.

It is a “completely new material – not only the thinnest ever, but also the strongest,” according to a press release from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announcing Geim and Novoselov as the 2010 recipients of the 2010 Nobel Prize for Physics.

“As a conductor of heat, it outperforms all other known materials. It is almost completely transparent, yet so dense that not even helium, the smallest gas atom, can pass through it.”

“One application that could consume a lot of material is composites,” said Eveleigh. In September, for example, Zenyatta Ventures signed a collaboration agreement with Ben Gurion University and Larisplast Ltd., an Israeli company, to develop concrete admixtures containing graphene.

“People are also working on infusing plastic, aluminum, resins and rubber with graphene to make them stronger, lighter, thermally conductive, electrically conductive,” said Eveleigh. “The properties of graphene are just incredible.”

Graphene infused concrete, for example, uses less cement, a major contributor of carbon dioxide emissions, cures faster, inhibits premature failure and withstands large forces produced during earthquakes and explosions.

Zenyatta is also working with the likes of Ballard Power to test and develop its high purity graphite for lithium-ion batteries and fuel cells.

The Albany deposit consists of two adjacent breccia pipes containing an indicated resource of 24 million tonnes grading 3.98 per cent Cg (graphitic carbon), and 17 million inferred tonnes grading 2.64 per cent Cg for a total of 1.5 million tonnes of graphitic carbon.

A logging road terminates seven or eight kilometres from the site, power and gas lines are located 30 kilometres away along Highway 11 and a labour force is available in the nearby Constance Lake First Nation and the Town of Hearst. The deposit is approximately 340 kilometres northwest of Timmins.

A preliminary economic assessment estimates an open pit mine life of 22 years and the production of 30,000 tonnes of purified graphite per year. Capital costs for the project are estimated at $250 million. Deeper resources would eventually have to be mined from underground.

Zenyatta Ventures expects to complete a pre-feasibility study this year. The junior miner is listed on the TSX Venture exchange and was trading in the 0.92 cent range in mid-January.