After more than a quarter century, people in Ontario’s energy sector are starting to take notice of Five Nations Energy, Inc. (FNEI).

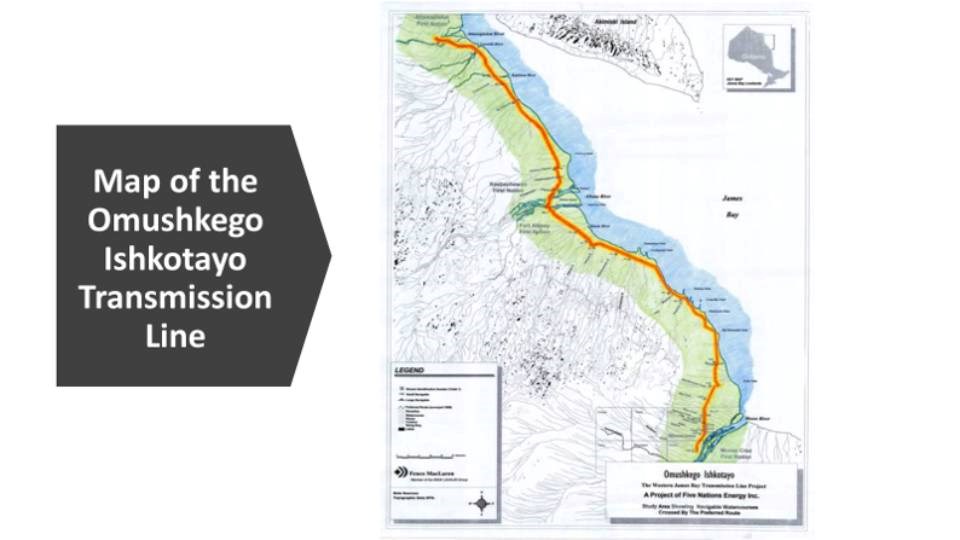

Five Nations is the corporation behind the Omushkego Ishkotayo Project, a 270-kilometre-long transmission line that powers Attawapiskat, Fort Albany, and Kashechewan.

It’s 100 per cent Indigenous-owned and operated, the only energy transmission company of its kind in Canada.

Pat Chilton, chief executive officer of Five Nations, said in the past few years there’s been an “upsurge” in discussions around energy, and he’s more than happy to tell his — and Five Nations’ — story.

- Anishinabek Nation’s economic development forum heading to the Sault

- Indigenous-owned electric company prioritizes giving back to communities

“Nowadays people are very curious,” Chilton told Northern Ontario Business, “especially around Ontario’s Ministry of Energy.

“People are interested in the ministry’s policies and the direction the government wants to go.”

In July, the ministry released its plans to meet the increasing demand for electricity, which is expected to continue rising through the 2030s and 2040s.

And in November, the province said it would boost its Indigenous Energy Support Programs by $5 million, with the goal of building leadership in the energy sector.

“With all the talk about what the (province) is doing, people want to know about our story, and how can they do what Five Nations did,” Chilton said.

Although Chilton said he likes to stay under the radar and let Five Nations’ work speak for itself, it’s safe to say the company’s history reads like a David-versus-Goliath story.

It began in 1996, at an assembly of the Mushkegowuk Council. A handful of Indigenous community leaders from the North rejected the Ontario government’s idea that James Bay communities couldn’t possibly connect to the province’s power grid.

Too difficult a project, they said. Difficult terrain. Little political will.

Thirty-seven times the group was handed an abrupt “no.” But 38 times the group, led by Chilton’s late brother Edward, dusted themselves off and kept on pushing.

“Well, we knew if they (the province) weren’t going to do it, then we would,” Chilton said.

Up until that time, communities on the coast were powered by diesel — large, loud, fume-emitting generators that ran night and day.

But community members couldn’t rely on the generator’s power, and due to the structure of government and Indian Affairs, it took years for any system upgrades.

Constant outages, surges, and repairs were the norm. When it came to development, James Bay communities were left years behind their southern neighbours.

To fuel the plants, about 5,000,000 litres (1,100,000 gallons) of diesel fuel was transported to the communities by barge, winter road and air. An environmental disaster waiting to happen.

Plus, with the low level of power output, the community couldn’t undertake any large construction projects, like community centres or arenas.

In short, without access to high-voltage power, the communities couldn’t grow and prosper.

To change people’s minds, Five Nations struck a consulting committee which travelled the coast, pitching their idea to remote Indigenous communities.

Connect to the existing grid by tying in at Moosonee, the committee proposed, and run transmission lines north up to the coast.

Then, just as they were honing their pitch, community members in one of those coastal First Nations raised concerns about disturbance to the natural habitat. There was a bit of back-and-forth between opposing sides at one particular meeting, and after frustrations — and tempers — started to rise, one of the community’s elderly women stood up, and asked for all the men to leave the room.

“As the story goes, all the men got up and left, and after about an hour and 20 minutes, they called the men back and just told them, ‘Listen, we need this line,'” Chilton said.

“The women looked at the men and said, ‘You’re going to build this power line. You’re going to go ahead and build it because it’s for the future of our kids.’”

With the blessing of its elder women, Five Nations was truly born.

History of Five Nations

Chilton’s brother, Edward, the original leader of Five Nations, was adamant that some of the thinking around northern development — especially when it came to hydro infrastructure — was badly outdated.

“Twenty-five, 30 years ago, the thinking people in government had was that you can't put a transmission line through muskeg,” Chilton said.

“But Ed said, ‘You’re darn right we can. Just leave it to the engineers.’”

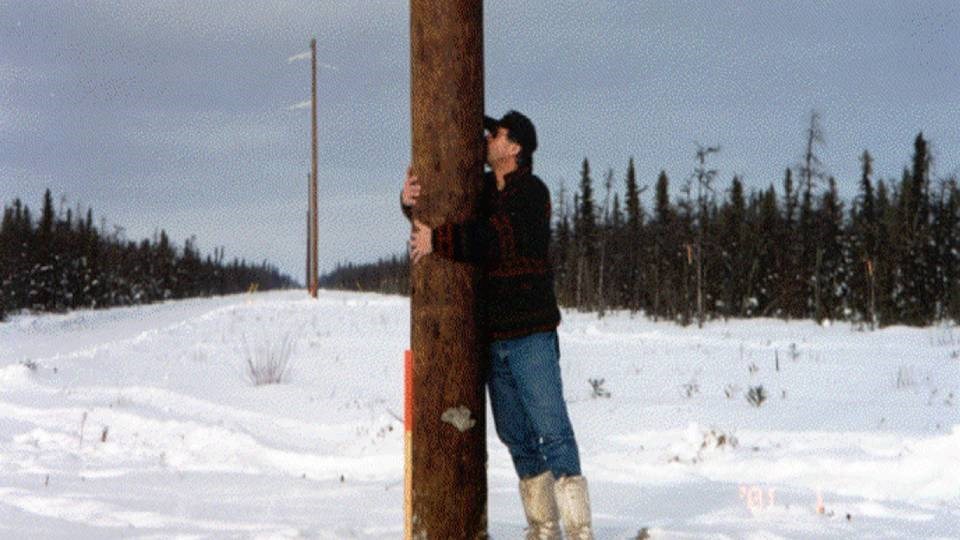

The Five Nations team got to work installing hydro poles through the wetlands, performing most of the installations in winter, when the surface was frozen.

The end result was a 270-kilometre-long transmission line from Moosonee north to Fort. Albany. Once that switch was flipped, it was diesel no more for those communities.

“They say that when (power) came on and the diesel generators were shut off, you could hear the birds singing,” Chilton said.

The team was also prescient enough to run fibre-optic cables along the lines, connecting those communities to high-speed internet.

A spinoff company, Western James Bay Telecommunications Network, also 100 per cent Indigenous-owned, now administers connectivity along the coast.

In October, they finished connecting fibre-op to Fort Albany, Kashechewan and Attawapiskat.

“Now, we can put in things like teleophthalmology,” Chilton said, noting that women no longer have to fly to Kingston, Sudbury or Toronto for mammograms. “It’s helped a lot.”

And health care is something Chilton knows plenty about.

Before coming over to Five Nations, Chilton spent the better part of 30 years in the health sector, including stints as executive director of Misiway Milopemahtesewin Community Health Centre in Timmins, CEO of Weeneebayko Health Ahtuskaywin in Moose Factory, and Health Canada’s hospital and zone director covering the Moose Factory area.

Chilton’s planning and leadership also earned him Health Canada’s Deputy Minister Award for Excellence in 2008.

A shift to the energy sector might be jarring for some, but Chilton said he had personal reasons to make the jump into uncharted waters.

The decision stems from his brother’s final days. In 2013, Chilton sat by Edward’s bedside as a battle with cancer left him unable to speak. But Ed could still move his hands, holding up five fingers, a gesture which Chilton understood to mean the Five Nations project.

“He was so proud of the work that he's done. He knew it had to be protected. And I told him, ‘I'll see what I can do.’”

When the CEO job became open, Chilton said he “jumped” at the opportunity.

“For me it was a way to live up to my commitment to my brothers, seeing what I can do to protect them and see the Five Nations flourish,” he said.

But the transition into the energy sector didn’t come without a few hiccups. It was an entirely different field than health care, for one. And Chilton said the role by its nature became political.

“It was a tough go,” Chilton said, adding that he spent six or seven days a week in the Five Nations office getting up to speed on the business.

“I mean, I had no background in energy; I’m no engineer,” he said. “So it was tough getting into the industry, learning what I could.”

Chilton credits his board of directors for lending plenty of support.

“I surrounded myself with great people, people who could not only help, but great advisors,” he said.

And despite his age — Chilton said he’s starting to feel every bit his 69 years — he doesn’t plan on moving back to the health-care sector, despite keeping an arm's-length interest in what’s happening in his home community.

“I’m not involved in health care anymore. I’m glad I made the transition to energy,” he said. “But I still like to keep an eye on things.”

Looking ahead for James Bay’s communities

Now, as the communities come online, and more power opens up more opportunities for Five Nations, Chilton sees the company playing a “pivotal role” in some of the province’s other major plans.

Namely, development of the Ring of Fire, a mineral-rich deposit in the province’s north which could contribute critical minerals to the burgeoning electric vehicle (EV) industry.

But like Five Nations’ struggle with government and businesses many years ago, it won’t be an easy win.

And there are questions whether running transmission lines to the area’s far northwest region would even be feasible, Chilton said.

“There’s five communities inland that are close to the Ring of Fire,” Chilton said. “We’d have to work with them and convince them we could deal with the infrastructure.

“But I think there has to be a lot of consultation first with the communities.”

That includes development, but on their “own terms,” Chilton said.

“The communities are angry with the way mining companies and the province and the federal government consult,” Chilton said, noting that he doesn’t speak directly for those communities.

“I think they don't like the idea, the concept of consultation being a matter of fly-in, fly-out type thing, or going in and out for a couple of days, or having dinner in Thunder Bay.

“What they want to see is the mining companies and the government experience what they have to go through on a day-to-day basis. The living off diesel, living in substandard housing, living with 28 years of boil water advisories, living with the lack of services.”

Development of the area, Chilton said, is a wide-ranging concept, one that can’t be “put in a box.”

“It would take a company like Hydro One to go there; they would have to reach out and put on the table that we're willing to help the First Nations,” Chilton said. “They’d have to bring everybody to the table, come up with a plan to make sure that the needs of the community members are taken care of.

“Then, regionally, you could bring in the people around (to discuss) the Ring of Fire,” he said. “That would be the way to develop the Ring of Fire. You're not going to do it any other way.”

For now, Chilton said he’s more than happy to keep Five Nations going. He can’t promise to slow things down, even though he admits he had a double bypass following a heart attack in June 2020.

He still keeps a busy travel schedule. The Five Nations group recently returned from an economic forum in Sault Ste. Marie where he had the opportunity to encourage others to stay persistent, just like his brother did 26 years ago.

“It's a good feeling,” he said. “It's actually a real good morale booster, in a way.”

Five Nations’ story is also the perfect subject for a yet-unnamed book, which Chilton just signed a contract to publish in March.

Although he’s keeping mum on the title, and some of the anecdotes included in the book, Chilton said there are hours' worth of transcripts from the people first involved in Five Nations.

Including the voices of the people who had been turned down 37 times.

The book, he said, will draw a lot from those conversations.

“I think the fact that once you start talking about it, and how important electricity is in transmission lines, the ownership of these lines, and the fact that there's money to be made for generations to come, people kind of sit up and take notice.”