A northwestern Ontario researcher is studying how Indigenous communities can sustainably harvest wild rice in an effort toward food sovereignty and the preservation of cultural tradition.

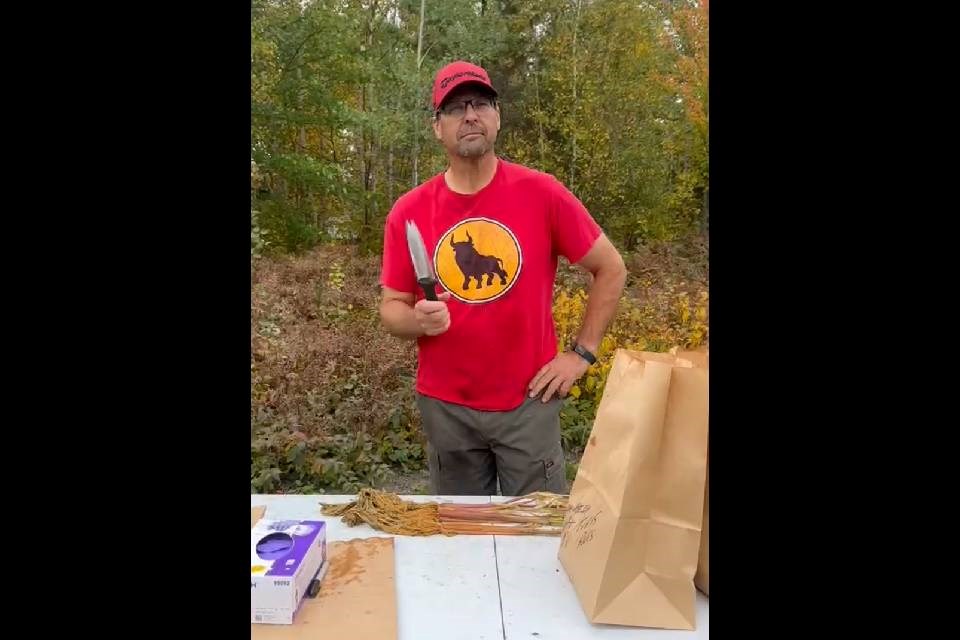

Dr. Vince Palace is an aquatic toxicologist, an adjunct biology professor at Lakehead University, and the head research scientist at the International Institute for Sustainable Development – Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA).

He’s currently leading a team of researchers in the project, titled ‘Multi-culture Agribusiness for Northern Ontario Managed by Indigenous Nations’ (MANOOMIN). It's being done in conjunction with Kenora Chiefs' Advisory — a cooperative of eight communities from Treaty #3 territory — Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, and Myera Group in Winnipeg, Man.

Manoomin is the Ojibwe word for wild rice.

In 2023, Palace and his research team received funding from the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund Corp. (NOHFC) to carry out the work.

But the IISD-ELA actually initiated the project a few years earlier as part of a greater effort to better connect with local First Nation communities, Palace noted.

In the past, when the ELA was strictly a government organization, its work tended to be very “insular,” he said. But after the ELA came under the wing of the IISD in 2014, the organization made a concerted effort to engage in more outreach.

“We're trying to gather ideas for projects that are of interest to not just the local communities, but also local Indigenous communities, and obviously, wild rice is a big part of that,” he said.

According to an Anishinabe cultural teaching, a prophet advised their people to travel west until they found a place where food grew on the water, Palace said. Because of this, wild rice is revered as culturally, traditionally and nutritionally significant.

“There's a big concern for the disappearance of wild rice, particularly in the Rainy River system.”

Through his work, Palace connected with Bruce Hardy, the founder of Myera Group, a Manitoba research organization focused on sustainable and intelligent food production systems.

Hardy’s interest in Indigenous food sovereignty led to Palace looking at how an aquaculture operation could help the communities in growing wild rice.

“Fish produce a lot of ammonia, and ammonia is really stable in terms of the type of nitrogen that wild rice needs,” Palace said.

“And so using the waste to fertilize the wild rice was the beginning of our project to see how much wild rice would you need to grow for a certain number of fish.”

They found it would require much more rice than is practical to neutralize the fish waste, he said. So they started looking at other options.

For example, could the extra nutrients from the waste be used to generate algae that could then be dried, pelletized and used as fish feed? Or could it be used as fertilizer to grow traditional medicines?

“So some of the waste fertilizes wild rice, some of it gets pelletized back into fish feed, and some of it produces traditional medicine,” Palace said. “So in that way, you generate a circular economy.”

The communities also wanted to see if they could re-establish rice in areas it used to grow — but this is where they encountered a problem.

“Because of the fluctuation in water levels, it's facilitated invasive cattails taking over there,” Palace explained.

“And it turns out, if you just throw wild rice into an area where there's cattails, the wild rice gets outcompeted. It's not very good at scavenging the nutrients, as it's not as good as cattails.”

Community members noticed that aquatic habitats with wild rice versus those with cattails attract different animals, birds and fish.

Among Anishinabe communities, much of that information is collected orally and passed down between generations, Palace said, but isn’t always accepted by western scientists. So they decided to use western research methods to try and quantify that data.

Researchers sampled water from each of the habitats and examined their environmental DNA (eDNA), which is composed of skin cells, feces or other DNA fragments left behind by organisms that use that body of water.

The eDNA is compared with DNA samples from known species, enabling researchers to identify what species are in the water without ever having to see them up close.

Researchers take a baseline sample in an area where there are cattails to identify the species, and then remove the cattails, reseed with wild rice and test again to see how the habitat changes, Palace said.

Throughout the experiments, Palace has been studying two varieties of rice: a true wild rice and ‘shatterless’ rice, which is considered a cultivated variety.

True wild rice is manually gathered using two sticks — a harvester uses one to bend the rice stalk over their canoe and the other is used to rap the stalk so the grains of rice fall into the canoe.

“It's a really ingenious way to harvest wild rice, because it’s not completely efficient,” Palace said.

“Some of those grains fall back into the water, which is really important, because wild rice is an annual plant; it has to be reseeded. So this traditional way of harvesting ensures that wild rice will be there again the next year.”

By comparison, shatterless rice doesn’t drop off the stalk. Instead, it’s planted in a flooded field, which is then drained, dried, and harvested by combine.

About half the wild rice sold and consumed in Canada is actually shatterless rice, commercially grown in flooded rice paddies in the U.S. But this method generates high amounts of methane gas, and so Palace and his team are looking into growing methods that use less water.

In their trials, researchers planted rice in tubs with soil and applied various amounts of water: 30 centimetres, 20 cm, 15 cm, 10 cm, five cm, or just saturated.

The true wild rice was very sensitive to water levels and grew best in the tubs with 30 cm of water, Palace said. That was expected, he added, based on community input and existing literature on the plant.

But the shatterless rice grew just as well in saturated soil as it did in tubs with 30 cm of water.

In future studies, he said, they’ll be “continuing to look at how that variety grows and whether maybe it's better at competing for nutrients with cattails versus the wild type.”

Community engagement has been invaluable to the process, Palace said.

Members often have different goals: some want the cattails removed and to reseed the areas with rice, while others want the cattails to remain so they can use them in activities like basket-making. It's important to listen to ensure the researchers understand this, he added.

In addition, community members have shared their knowledge about what species frequent certain areas, adding to the researchers' understanding of their data. Youth have helped with pond-reseeding efforts and have learned to use western science tools.

“We're trying to be respectful of the way different ways of data are collected,” Palace said.

Palace has wrapped up year three of the five-year portion of the project funded by NOHFC, but he can see the initiative continuing well beyond that timeline. His team is in discussions with multiple potential partners to further the work, including the University of Minnesota-Duluth, the St. Croix Wetland Research Center in Minnesota, Voyagers National Park, and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Separately from Palace’s research, there is also the work being done by Myera, which is interested in collaborating with the communities on value-added wild rice products, including wild rice flour, rice cakes, protein shakes, bannock, and other foods, both for their own consumption and for sale outside the communities.

Despite the important implications of wild rice on Anishinabe culture, the traditions associated with the staple are dwindling, Palace said.

That’s why he’s hopeful his research can prove useful to the communities looking to re-establish the crop for future generations.

“It's really an important goal because, if you look at the average age of rice harvesters in Indigenous communities, most of them are in their early to mid-60s, some of them even into their ’70s, and so there's a loss of this cultural ability to be able to harvest the wild rice,” Palace said.

“And so we'd like to provide some tools by which the community can rescue that traditional way of life.”