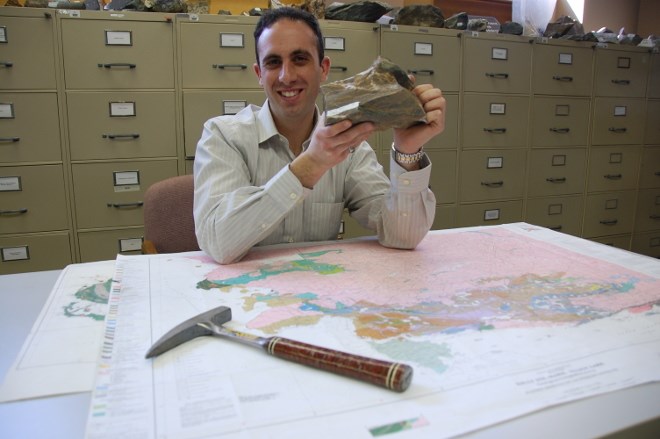

At the Ontario Geological Survey’s Resident Geologist Office in Sault Ste. Marie, staff is undertaking a project to catalogue and digitize mining data that’s been unavailable to the online public — until now.

District geologist Anthony Pace said a mining company will often donate data to the Ministry of Natural Development and Mines (MNDM), such as original mine or surface plans, after a mine shuts down, or an exploration project comes to a close.

It’s information that could be valuable for future prospecting or exploration on the site, but it’s only available in limited format.

“If we lose that data, the actual original data, it’s gone,” Pace said. “We don’t even have a form of backup for it.”

So staff at his office has started cataloguing it, with an aim of also digitizing it and putting it online, so that it’s accessible for everybody.

The Sault Ste. Marie office oversees a district that extends from just east of Elliot Lake to south of White River, and west of Chapleau.

Currently, much of the exploration and development activity is taking place mostly in the Wawa-Dubreuilville area, where companies like Red Pine Exploration, Argonaut Gold, and Richmont Mines are making news for their mining activity.

Often, that data can be the information that companies want coming into a new area of exploration, as it can contain crucial details associated with a property, Pace said.

“That’s usually what we call our gem maps because that’s typically the stuff that companies will keep confidential,” Pace said. “They won’t file it for assessment with the MNDM; they’ll just file what they’re required to file, and sometimes there could be some information that they’ll have that they just didn’t want to go public.”

In some cases, that information can be the key that kickstarts a new exploration project, Pace said.

It’s valuable because using information already discovered by their predecessors, prospectors can save time and money because they already have a baseline to work with, he added.

“We’ve had projects in my district start mainly because of the donated material that we’ve had,” Pace said. “They were able to use this data based on this data that we catalogued, and if it wasn’t for that, they probably wouldn’t have acquired the property.”

In the late 2000s, as the price of uranium rose significantly, there was a “big push” for uranium companies across Canada to look for new sources of the base metal, Pace noted.

As a former producing Ontario uranium mining camp, Elliot Lake became a hotbed for prospecting.

In the years since production had occurred there, the resident geologist’s office had amassed exploration data donated by companies that had worked in the area as far back as the 1960s and 1970s.

It was information that wasn’t available anywhere else, and no one had looked through it for years.

“We just happened to be going through a lot of that stuff and cataloguing it, and because of those maps, companies were able to put together exploration programs,” Pace said.

A big part of the Resident Geologist Office’s mandate is not only making exploration data available to everyone, but making it available in a format that people can actually access and use, he added; “otherwise, what’s the point in keeping it?”

And that’s why it’s important for companies to contact the Resident Geologist’s Office in the district in which they’re exploring, since staff there can guide them to helpful information.

The Sault Resident Geologist Office has so much information on hand, the cataloguing and digitization process is “probably a never-ending project,” Pace said.

But the goal is to sort the information by priority, in terms of what information they think will be most valuable and useful, and work from there. The hope is that the data contains a gem, somewhere, that could lead to a half-million-dollar diamond drill project and potentially new mining opportunities for the area.

“If we want to continue to have people prospecting within our districts, we have to make sure if there’s any new data available, it’s there and they can actually acquire it,” Pace said.