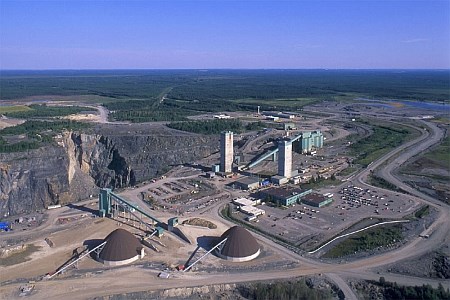

With the closure of Xstrata’s Kidd Metallurgical site having officially begun May 1, Timmins’ municipal and union officials are working to determine how to survive beyond what has already been an enormous blow.

With roughly 640 jobs leaving the city, local gears have shifted from attempting to halt the closure to working with various levels of government on addressing the root causes of Xstrata’s decision while also attracting new industry to the site.

As such, Timmins Mayor Tom Laughren has been working ardently with the Northern Ontario Large Urban Mayors (NOLUM), the provincial Ministry of Northern Development, Mines and Forestry, and the federal government for solutions to both problems.

The heart of the matter, he says, is that while the demand for resources from China and India will rise, and Northern mining opportunities are plentiful, the underlying cost structure in Ontario makes processing prohibitive.

“At the end of the day, we need to decide as a province and a country whether we just want to be miners or if we want to do the whole gamut to value-added products,” asks Laughren.

“If you look at the Northern Ontario Growth Plan, it talks about opening the North up to opportunities for manufacturing, but we believe we have manufacturing jobs at the Met Site we’re watching leave the province. You can talk the talk, but you have to walk the walk, and we need to sit with government to see how we can do that.”

The NOLUM representatives, minus Thunder Bay Mayor Lynn Peterson, met with federal Industry Minister Tony Clement to address these issues in April. They walked away with assurances of concern and an interest in helping, but no commitments. Regardless, Laughren says Clement’s leadership will be needed to connect Timmins’ core concerns to the appropriate government figures.

Progress with the province has been similarly slow. In discussions between Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty and representatives of the city, the union and Xstrata in mid-April, company officials outlined four specific factors for the Timmins site’s closure: globalization, the high Canadian dollar,the cost of power and Ontario’s increasingly strict environmental regulations.

While the province’s promise of a lower three-year power rate for industrial projects was a good start, it comes too late and with too little meat to have any impact on Timmins, says Laughren.

As an additional step, the province has announced $225,000 for the city to spend on a feasibility study to outline the Met Site’s assets, environmental concerns and marketing opportunities.

This is far too little for Ben Lefebvre, chairman of Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) Local 599, whose jobs are being eliminated by the closure.

Calling the study “mere window dressing,” Lefebvre points to similar efforts in Smooth Rock Falls, Hearst and Opasatika, where major job losses in forestry sparked provincial funding for similar studies, with no lasting results.

Also, the infrastructure at the site won’t last beyond the end of the year, predicts Lefebvre, as the frost will likely lay waste to the equipment as it goes unused through the winter months. This puts a very real deadline on finding alternate uses for the site, with the wheels of government turning much slower than the union would like, he says.

Considerations for these kinds of alternate uses have included the red-hot Ring of Fire, where Cleveland-based Cliffs Natural Resources is tentatively committing to spending $1.3 billion on developing North America’s only chromite mine.

Very brief, preliminary discussions have been held between the city and Cliffs. However, the company wouldn’t need the facilities for another five years, meaning the usefulness of the remaining infrastructure would be questionable, says Laughren, who still sees the potential to produce stainless steel in the North.

A study commissioned by the Timmins Economic Development Corporation has shown the site’s closure will lead to the loss of 1,162 direct and indirect local jobs, and $54.5 million in wages.

However, for the union, the issues extend beyond the “devastating” financial impact of the closure.

In particular, Lefebvre is concerned about Canada’s future ability to independently produce key metals, especially since Hud-Bay Minerals will close its Flin Flon copper smelter in July, leaving the Horne smelter in Quebec as the only one of its kind left in Canada.

Should Horne shut down, Canada will be left at the mercy of other countries for metals such as copper, which is already significantly above its historical price levels, he says.

“It’s a scary potential reality,” says Lefebvre.

In the meantime, the union plans to continue moving forward with plans to convince the province to change its mind in allowing Xstrata’s decision, or to at least secure a one-year moratorium on closing the site while also restoring feed.

Regardless of what happens, however, Laughren says continued efforts by groups and individuals from throughout Northern Ontario is necessary.

“If we do nothing, then we’ve given up,” says Laughren. “If we do try something, and at the end of the day we can’t overcome the hurdle of being uncompetitive, at least nobody can accuse us of not trying. To be honest, I think it’s a shame we’re closing the newest smelter built in Canada, and it tells me we can no longer be competitive in the refining and processing business.”