Sixteen years after Weyerhaeuser permanently closed the corrugated paper mill in Sturgeon Falls, a new book is taking a comprehensive look at the myriad, complex ways in which the shutdown impacted the community.

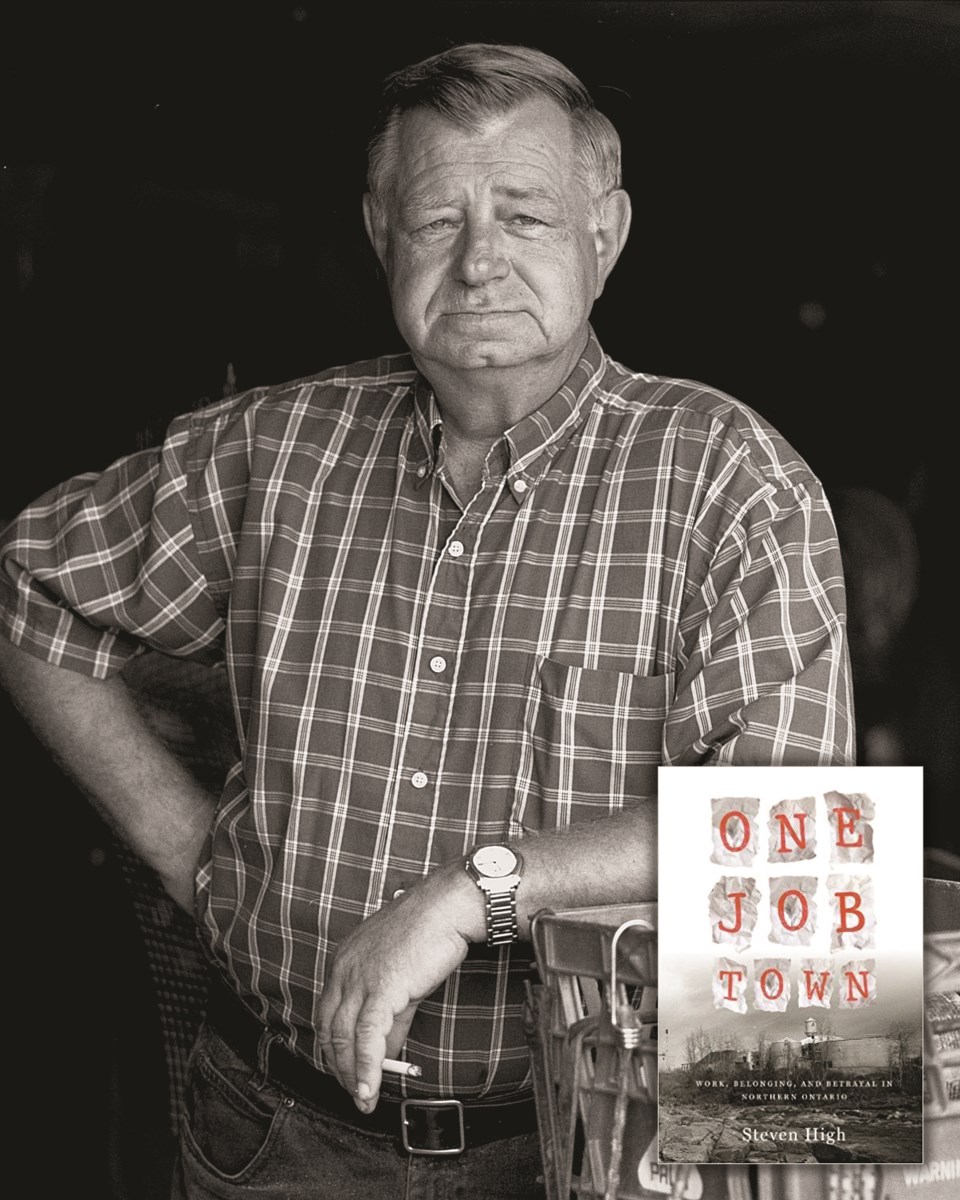

One Job Town: Work, Belonging and Betrayal in Northern Ontario is the culmination of years of in-depth research by Steven High, whose interviews with 55 former mill workers, managers, and superintendents form the heart of the book.

“It began as a study on the mill closing, but it became a story of the mill itself throughout its lifetime, right from 1898 onwards,” said High, a researcher and history professor at Montréal’s Concordia University.

“It’s a really interesting story that shows how important Northern Ontario resource development was, not only in terms of Ontario or Canadian history, but also in a wider history.”

High had only recently accepted a professor position at Nipissing University in North Bay when Weyerhaeuser announced, in October, 2002, the permanent closure of the plant, which employed 150 and had been in continuous operation since 1898.

One of his students, whose father worked at the mill, suggested he look into the closure, and High set to work, teaming up with documentary photographer David Lewis to chronicle the process.

Fully half of the workers he asked declined to be interviewed for fear of saying something that would jeopardize efforts to revive the mill, which, at the time, was a faint possibility, while others expressed hope that a new buyer could be found. But that never happened and the mill was eventually demolished in 2004.

Most interview subjects described a “deep sense of betrayal” at the closure and the way in which it happened, High said. At its shutdown, the mill was still generating revenue and had a supply contract through another nine months of production. But citing a need to make the company more profitable, Weyerhaeuser closed it anyway, with very little notice to employees.

As the community’s largest employer, where generations of families had worked, it was a huge blow to the small town of 6,000 people.

“When mills close, it is an economic story, but it’s also a story about cultural erasure where that history is also being demolished,” High said.

Boxes of documents and photographs detailing the mill’s history were destroyed by the company; employees’ requests to preserve them as part of the town’s legacy were declined. However, the documentarians were able to rescue some items that had been saved by the interviewees themselves, along with a box full of company newsletters that were furtively passed to them by a salaried employee.

Those items, along with High’s interview recordings, are now available to the public via the Sturgeon River House Museum.

For residents, the closure churned up memories from the Great Depression, a time when the mill remained closed for 17 long years, leaving close to three quarters of the population on relief and nearly devastating the town, High said.

Many feared a similar scenario would play out again with the plant’s permanent shutdown, but things had changed dramatically over the decades, he said. Sturgeon Falls has been reborn as a bedroom community for commuters to North Bay and Sudbury – which bookend the town – and the town found itself, if not prosperous, then at least stable.

“Life went on, which was surprising to mill families because they still saw the town as mill town,” High said. “It had already transitioned away from that, because the mill had declined over 30 years.”

The number of employees peaked at 600 in the 1960s, but production gradually decreased over the years, and by the time the mill closed for good, it employed just 150, he added.

“In a way, the transition had occurred unnoticed for many years within the small community, and so when it finally closed, it didn't have the same kind of economic impact as it would have had in the 1960s,” High said.

Sturgeon Falls’ story mirrors those of hundreds of other towns and cities across the North, and around the world, which makes it far from rare, he noted. But what is unique is that it’s a story of Northern Ontario, which High calls the “least researched region in Canada.”

“I think of Northern Ontario as the lost region,” High said. “In a way, Northern Ontario is the largest provincial north, and it gets hidden by this label called Ontario, and that has made the challenges we've had in the last generation economically pass in silence.”

“It hasn't been seen in the way that it should be, and so I think this is making it visible, making it audible, countering this erasure that happens locally but also regionally.”

The Sturgeon Falls Library hosted a public launch of the book on June 9, with High in attendance.

One Job Town: Work, Belonging and Betrayal in Northern Ontario can be purchased online from University of Toronto Press, Indigo, and Amazon.