Ottawa's new region-wide approach to Far North development shouldn't interfere with Noront Resources' timetable to put the first mine in the Ring of Fire into production by the middle of 2025, said the company CEO.

Alan Coutts said he has no reason to believe that the federal Regional Assessment process will delay the start of operations at the Eagle's Nest Mine based on his conversation with Natural Resources Minister Seamus O'Regan.

"In talking to Minister O'Regan, we're being led to believe this could get done over a two-year period."

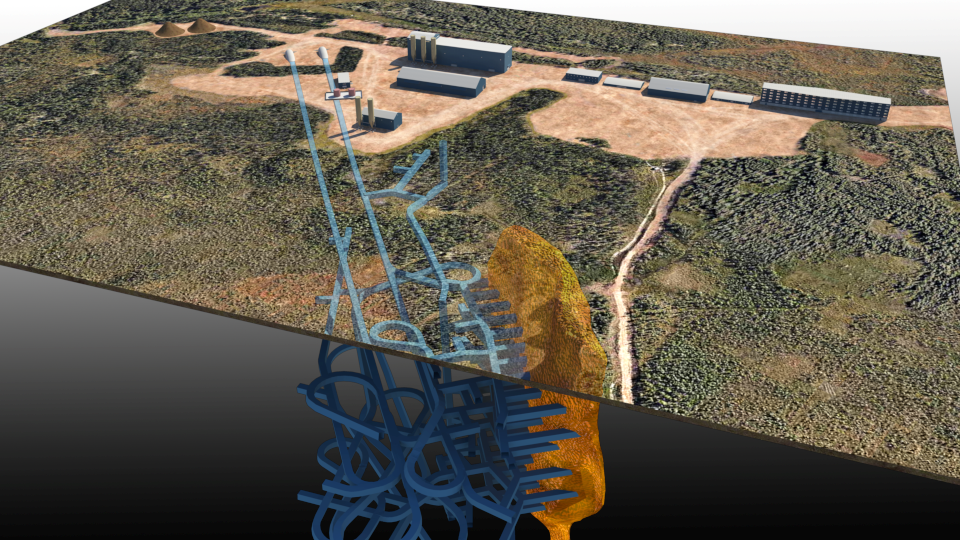

That neatly fits into the company's project timeframe which shows construction of the long-awaited North-South road slated for mid-2021. Noront's Esker exploration camp and its high-grade nickel and chromite deposits are 360 kilometres from the nearest road.

The four-year road build is expected to be finished just prior to the start of nickel, copper and platinium group metals production at Eagle's Nest.

Eagle's Nest is the first of a pipeline of upcoming mine projects that include the Blackbird and Black Thor chromite deposits to be brought online in conjunction with a proposed ferrochrome processing plant in Sault Ste. Marie.

Want to read more stories about business in the North? Subscribe to our newsletter.

With six road and mine environmental assessments underway, bankrolled by the province and Noront, how this new regional assessment will impact the current studies isn't exactly known.

Coutts' understanding is that O'Regan and provincial Energy, Mines and Northern Development Minister Greg Rickford have a "shared vision" in their approach to permitting and development that, he was assured, shouldn't affect the environmental work that's already been done.

"They're very motivated to get this done quickly so it can feed into the provincial assessment," Coutts.

"I don't see any threat of that regional assessment slowing down the provincial approvals and ultimately construction."

The Trudeau government's new process under the Impact Assessment Act, announced in February, takes a more holistic approach to large-scale projects like the Ring of Fire, taking into account not just environmental impacts but impacts on local economies, health, social issues, and Indigenous rights.

In some circles, the legislation is viewed as dragging out the review process for major projects, as more Indigenous communities across the northern landscape would have to be engaged.

But beyond Noront's closest development partners in Marten Falls, Webequie, Aroland First Nations, Coutts reconciles that this tiered approach is now an accepted fact of life in developing mines in the 21st century.

"It's true. You're fighting an uphill battle if you try and limit the number of people you talk to."

He regards the regional assessment as a useful exercise to capture values that otherwise wouldn't end up in an environmental assessment report for a mine.

"What we don't want are things getting bogged down forever in permitting. As long as it's done on a consistent, timely, coordinated basis, we're fine with it."

The discovery of chromite in the region was made in 2007 by the late Richard Nemis, then-president of Noront.

But since then, very little has been accomplished by way of road or mine construction. Under the previous provincial government, bureaucracy and endless discussion prompted Cliffs Natural Resources to bolt from the Ring of Fire in 2015.

Coutts, who left Xstrata Nickel to join Noront seven years ago, contends it's high time to show signs of tangible activity, beyond just studies.

"I think we really have to demonstrate physical progress soon. Ultimately, it's easy to say to potential investors, hey, look we've got all these EAs progressing and we're doing it in innovative way where the communities are leading it themselves. The guys with money say, So what? Tell us when the road's built."

Signs of momentum are there.

A 20-kilometre section of Highway 643 has been upgraded at the bottom end of the proposed North-South road near Aroland and a major rail connection.

The next piece is upgrading a 70-kilometre stretch of forestry road, tentatively scheduled for this fall, before new road construction would begin in 2021.

With Marten Falls and Webequie in charge of the environmental assessment, routing, and contractor selection on the sections of proposed road crossing through their individual territorial lands, Coutts said that inclusive approach brings him encouragement that the roads will be completed on time.

The dual-use industry and community access road will be 60 metres wide within a 100-metre cleared right-of-way to accommodate heavy dump trucks carrying ore down from the mines as well as cars, vans, small trucks and motorcycles.

To critics and conservationists, roads, powerlines and infrastructure related to a Far North mining rush represent pathways that will irrevocably disturb the region's fragile plant life and ecosystem.

"Don't get me started," said Coutts. "When you boil it down and say, it's a two-lane gravel road, yeah, you kind of shake your head. Our country makes things complicated."

More grief was directed at the Ford government's recent move – through the passage of Bill 197 – to change the provincial environment assessment process to expedite approvals on projects, which created more waves with environmentalists and First Nation communities like Attawapiskat and Fort Albany, downstream of the Ring of Fire.

They contend it's a roll-back of environmental protections that will put the Far North's environment at risk, all in the name of cutting red tape in supporting economic interests. The communities further argue the province has overstepped its jurisdictional boundaries and disrespected their inherent Aboriginal and treaty rights and their connection to the well-being of their homelands.

Coutts said their concerns are legitimate but he prefers to heed the guidance from their First Nation community partners.

On matters Noront can control, Coutts said they've done their level best in listening and alleviating any local concerns through a system of "checks and balances" in their Eagle's Nest mine design.

The low-profile underground nickel mine will not expand beyond its current footprint.

All the water used in the mining process will be recycled in a closed loop system. Containment ditches will capture any surface spills and effluent runoff to ensure there's no ground water contamination or migration off site. Monitoring wells will be overseen by local First Nations.

There will be no mine waste storage facility on the surface. All tailings will be shoved back underground as cement backfill.

In powering the mine, diesel generation will be employed initially, but Coutts said there will be a move toward cleaner energy technologies such as underground electric vehicles to reduce ventilation costs. Wind and solar technologies will be utilized where possible to reduce their greenhouse gas signature.

"It's not a bad process if people can lay out their concerns early on. You can adjust and take those concerns into account, which we did," Coutts said, "as long as you can approach this reasonably, and there's not underlying motives to try and delay or stall the development."

Despite his frustration over the years at the snail's pace of progress, Coutts said he takes his cue from Noront board member JP Gladu's message of economic reconciliation and how making First Nations full project partners goes a long way to the health and well-being of communities.

Coutts agrees that training, education and exploration camp job opportunities, making the communities part owners in Noront, and having them oversee the environmental assessments, routing and construction of the supply and haul roads provides an entrypoint into the modern economy.

"I think most people share that vision. As long as we can do this in a way that's not prescriptive or bullying and is really inclusive, I think we've got a generational winner on our hands."

Coutt said that's the reason he and chief development officer Steve Flewelling have stuck it out.

"We're not guys that kinda want to sit around for five years waiting for permits. We believe in this project and the good it can do for Ontario and Canada, and we're kinda determined to get it through."