By early 2024, Steven Beites believes his research team will have a working robot that can pick up and place modular housing panels in the construction of a single-family home.

It will just be a prototype at that stage, and there will be plenty of work still to do before the machine can be deployed to a build site.

But it will mark a major milestone for the multi-year project that's poised to help revolutionize the residential construction industry in Northern Ontario.

“The focus is really to assist when it comes to construction,” said Beites, an associate professor at Sudbury's McEwen School of Architecture.

“So, how do we start to integrate automation into the construction process as a way to design faster and design more cost-effective buildings.”

Want more business news from the North? Sign up for our newsletter.

Two years ago, Beites received a grant from the New Frontiers in Research Fund, which enabled him to push forward on the development of a cable-driven parallel robot (CDPR), a computer-controlled robot that uses a system of cables and pulleys to perform a specific function.

Since then, his team has worked on the mechanical design of the system, the control mechanism, and the development of software, among other components.

Its aim, he said, is to be able to build modular homes in communities throughout Northern Ontario.

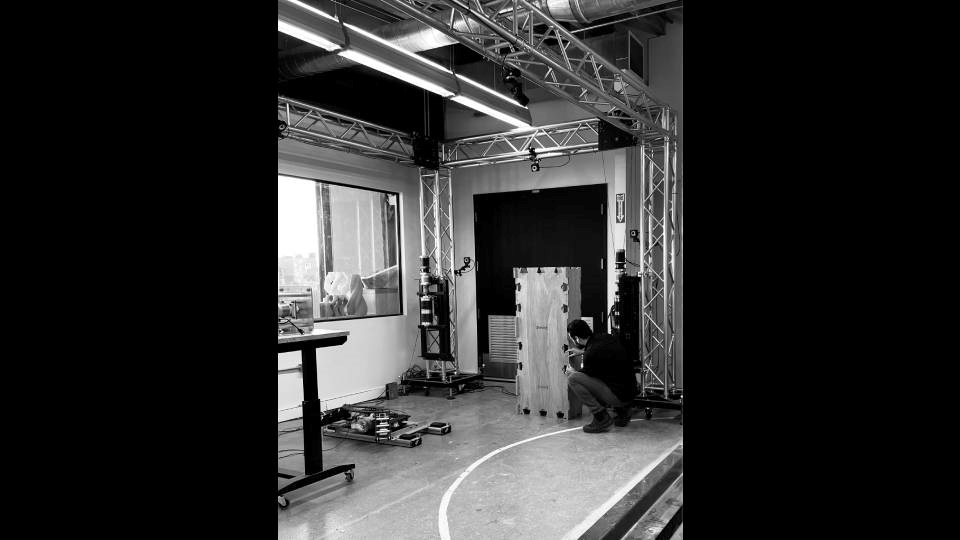

The first prototype was built this past July. It's housed in Beites’ robotics lab at the downtown McEwen School of Architecture.

Now, he said, their focus will shift to fine-tuning its functionality while designing the tools it will use in the build process.

“You need to have the ability to be able to pick up a prefab panel or prefab block in a way that has to meet real, practical requirements,” Beites said.

“In essence, it needs to pick up a panel in a certain location, has to have the capacity to rotate that panel from a horizontal to a vertical, and then position it into place.”

The introduction of new technology to boost productivity isn’t anything new, Beites said, pointing to the automotive industry as an example.

That sector began using robotics as far back as the 1960s, and automation has since become an integral part of a car manufacturer's assembly line.

Canada's construction industry lags by comparison, Beites said, although he acknowledges getting widespread adoption of new technology by the sector could be challenging.

Yet other countries are making strides in this area.

In Sweden, 90 per cent of new single-family homes are built using modular construction, Beites said, while in Japan builders have adopted Toyota's LEAN manufacturing philosophy that favours efficiency and a reduction of waste.

At home, Beites believes technology could have a big impact on a sector that's facing twin housing and skilled labour shortages.

In Ontario alone, Bill 23, the More Homes Built Faster Act, 2022, calls for 1.5 million homes to be built over the next 10 years — a feat Beites called "really difficult to achieve with current methods of construction” — with some studies suggesting we need between 70,000 and 100,000 skilled trades workers to meet demand.

Integrating technology into construction practices could have the added benefit of attracting a younger workforce that's grown up with tech all around them and is enticed by the opportunity to work with leading-edge innovation, he added.

But using more easily navigable construction techniques, such as modular building and plug-and-play technology — as Beites is aiming to do with his CDPR — also means that the sector won't need to rely so heavily on workers skilled in the trades.

A key driver of his project is that the CDPR will be so easy to use that it won't require anyone with specialized training to operate it.

That means that the CDPR, which will be portable and not reliant on the electrical grid to operate, could be set up in any Northern Ontario community, and immediately set to work by community members, building new homes, communal spaces, and other buildings.

“Construction here in the North is very different than in the south in terms of the season, in terms of when you can build,” Beites said.

“So the CDPR is really beneficial in regions by which road access can be difficult and the speed of construction's really critical.”

Beites is hopeful that his team will have a fully working prototype some time between year's end and early 2024, at which point they'll be able to demonstrate the CDPR's capabilities at full scale for industry partners, government representatives and other stakeholders.