Sudbury’s consolation prize for missing out on the Ring of Fire ferrochrome smelter could be a lithium processing plant.

Lepidico, an Australian lithium development company, is evaluating two industrial properties in Sudbury for a chemical plant that produces lithium carbonate, a key ingredient in the manufacturing of lithium-ion batteries.

The Brisbane-headquartered company is having plant design, engineering and baseline environmental work done at two undisclosed properties in preparation of a Phase One production plant.

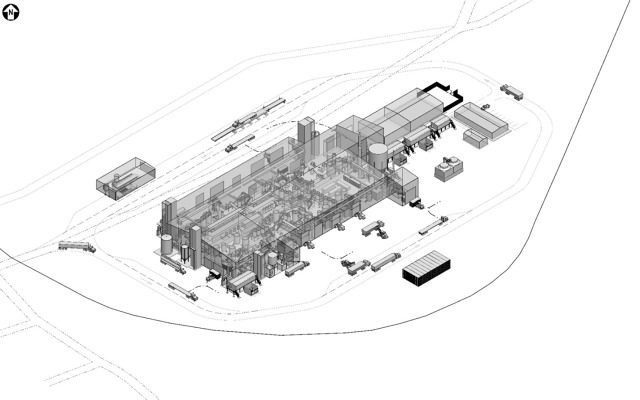

The 36,000-square-metre plant would produce 5,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate annually and provide employment for 70.

The operation would be a hub of activity with lithium concentrate arriving in Sudbury by rail and truck from mining operations in Canada and overseas. The processed product would be exported to battery manufacturers in Asia.

If the permitting and approvals process goes smoothly, the plant could be in production by 2020.

Down the road, Lepidico is studying the construction of a 10,000-tonnes-per-year plant.

The company is spending the remainder of this year and into 2019 working on a plant feasibility study, securing permits and sources of lithium supply, and raising financing for the plant, estimated last year to be US$45 million, but for a smaller plant.

The location of the sites isn’t being disclosed pending the signing of commercial agreements.

“It’s premature to say at this point,” said Joe Walsh, Lepidico’s managing director, who moved from Brisbane to Toronto this year where the company has set up a downtown office.

According to company documents, the preferred property is a private industrial park that has all the power, water, gas and rail connections that the company wants. The property owner is working with Lepidico to see if they can tap into government funds to upgrade the power and gas connections.

On financing for the plant, Walsh said other similar projects have been funded through a combination of pre-paid off-take (supply) agreements from battery manufacturers, government grants, and equity. Galaxy Resources, a $1.2 billion Australian-listed company, took a 12 per cent stake in Lepidico last year.

The backbone of Lepidico’s growth strategy is a patented, home-grown technology, called L-Max, which extracts lithium from lithium-bearing hard rock called lepidolite.

Lepidolite is in growing demand for conversion into lithium carbonate.

Walsh said five or six years ago, the annual growth in the global lithium market was in single digits. There was no incentive to bring new production on stream.

Lepidolite usually ended up on the mine waste pile. It was too difficult to process and filter out all the impurities.

That’s all changed with the explosion in demand for minerals used in green-tech applications, like cobalt and lithium.

The company had been running mini-mill tests of L-Max at their Brisbane offices and wanted to upscale into a demonstration-scale plant that was small enough to manage the risk but large enough to generate a return on investment.

“The next stage is to secure sufficient mineral resources to be able to build a full-scale plant, which may be five to eight times bigger,” said Walsh.

The plan is to have material feed for the plant coming from multiple sources through agreements with lithium miners in Canada and abroad.

The company has a tentative off-take agreement with Grupo Mota, operators of the Alvarroes lepidolite mine in Portugal.

Lepidico also struck an off-take agreement last year with Avalon Advanced Materials of Toronto.

That company plans to build an open-pit lithium mine, north of Kenora at Separation Rapids. About 20 per cent of the resource there is lepidolite.

Walsh said consideration was given to build the plant in Kenora, but logistics weren’t working in their favour. Sudbury has all the transportation, infrastructure and supply that they require.

“The logistics are better in Sudbury than Kenora, and getting our products to market is more straightforward as well.”

The Sudbury area also has an abundance of the consumables they need for the plant’s processing system, namely sulfuric acid and lime.

He extended credit to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines for introducing them to Ontario during an international trade mission. Ministry officials also identified potential plant sites for them.

Walsh said their objective is to create a chemical plant that produces no waste.

Their hydrometallurgical process produces saleable byproducts such as sodium silicate and sulphate of potash.

One particular residue from the L-Max process is a white, powdery alkaline that may be suitable for landfill reclamation when mixed with biomass to allow vegetation to grow in acidic environments like Sudbury.

The company is working with Knight Piesold Consulting, Laurentian University, and the City of Greater Sudbury on a commercial use for the residue.

If that’s proven to be the case, the company can eliminate the need for a residue storage facility at the plant.

“That would mean the only emission from the plant would be steam,” said Walsh.

“It will be a very low emission facility producing a suite of green products. If we can make that residue a product, then there’s no waste.”

An emailed response from the City of Greater Sudbury and its development corporation said the municipality has been working with Lepidico for almost a year but directed all queries on the development back to the company.